A short story

Hey everyone,

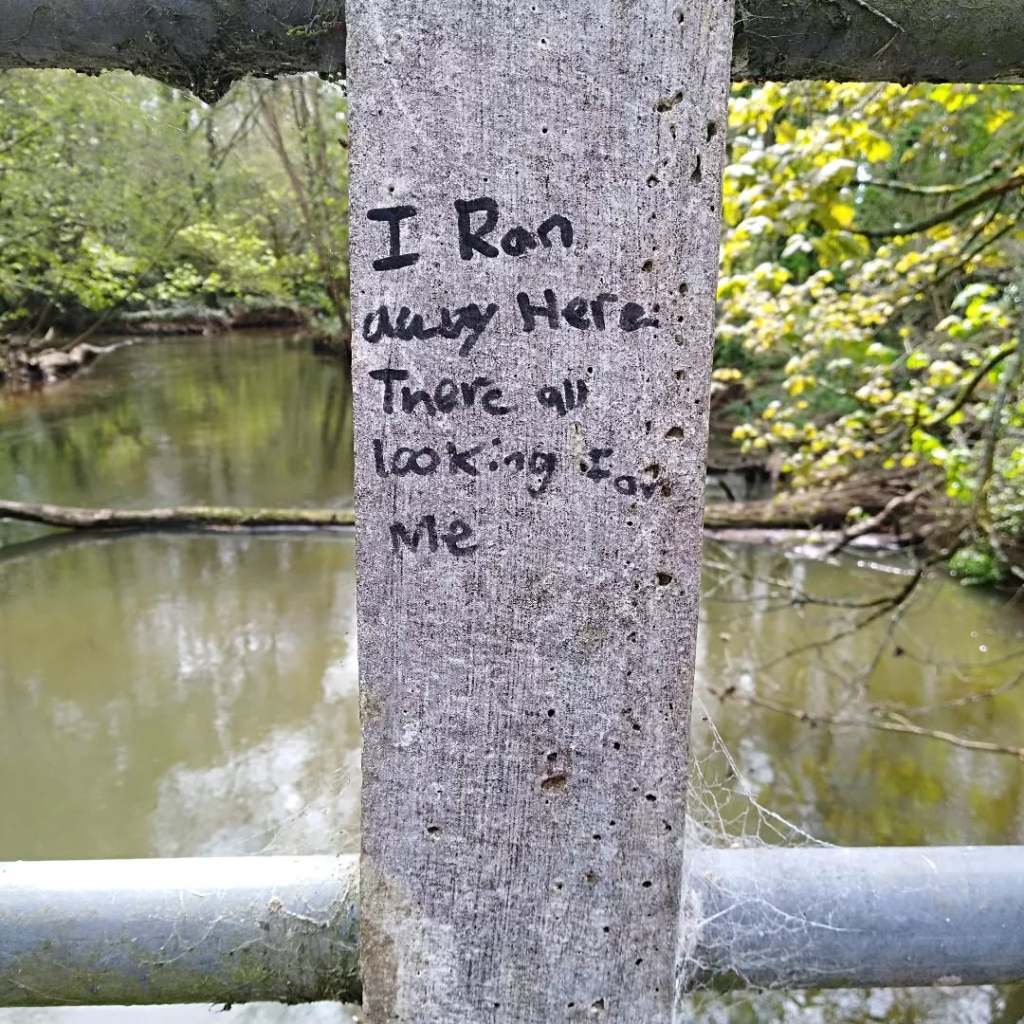

I hadn’t quite finished the post I had in mind for today so I’m going to share this short story with you instead. And yes, that does mean the writing is flowing again! More on that next week. I wrote this piece in response to a prompt on Medium, which instructed you to go outside and take a random photo then write a story inspired by it. This graffiti was added recently to one of the poles on the bridge down the lane from us. I thought it made a cool photo and a cool short story prompt so here we go. (This is only a second draft story and I do intend to polish it up a bit more in the future.)

What Happened To Pip Collins? (Working title)

The ghost hunt starts at the little stone bridge, just a ten minute walk down the lane. My older brother Ed photographs the graffiti and starts scribbling in his school notebook while I pluck catkins from the young ash trees and toss them into the shallows.

For a long time, this little note, this graffiti from another time, was the only clue in a missing person’s investigation but three weeks ago, another note was found on the wall of an abandoned mill. The mill is on the other side of the Stour, what we call the ‘big river’ and it was my brother who made the connection to this one. He immediately knew what he was going to do his local history project on: the disappearance of ten-year-old Philip Collins in 1978.

He had a hard time convincing his history teacher but he didn’t give up, arguing that everything that happened in the past is now history and if the boy vanished locally then that makes it local history. For the record, I think he is right about this. Plus, I really want to see a ghost.

Bored of tossing catkins, I indulge in a quick game of pooh sticks, snatching up twigs and throwing them over the mossy bridge, before darting to the opposite side. Ed rolls his eyes and I sense his impatience, but I see no urgency in the putting away of childish things. My first twig gets stuck on the large fallen tree that cuts the shallows in two. My second bobs up and over it, and the third never emerges from under the bridge.

Meanwhile, Ed consults his notes, reading from a newspaper clipping he found online, printed out and stuck into his project book:

‘Ten-year-old Philip Collins, known by his family as ‘Pip’ was last seen leaning over the railings of the small stone bridge on Hurn Court Lane, Hurn Village, Christchurch.’

I drift towards Ed and peer over his shoulder. He has the photograph of Pip in his project book too. We both stare at the black and white shot of a beaming, dark-haired boy who looks like the cheekiest kid who ever lived. His huge grin, his lips pressed together as if swallowing laughter, and his shining eyes all suggest a little rascal. He’s wearing dark coloured shorts and wellington boots, and a dark zip up cardigan which looks too small for him. He’s clutching one of those tiddler catchers, you know, a colourful net on a bamboo stick. Ed reads on:

‘A couple walking their dog across the bridge reported the sighting the following day after the alarm had been raised. Mr Weathers told the police that the boy was leaning over the railings and appeared to be alone. They said hello and walked on. They walked their dog in Ramsdown Forest on the opposite side of Christchurch Road, and when they later walked back the same way over the bridge on Hurn Court Lane, the boy was gone. He had however left a note on the railings of the bridge.’

Ed runs his finger over the next photo in his book, one taken back in 1978 of the graffiti left behind. He brings up his phone and compares pictures. It is amazing how the writing has been preserved over time. It’s even more amazing that a second note was hiding on the side of the mill all these years.

‘What next?’ I ask my brother.

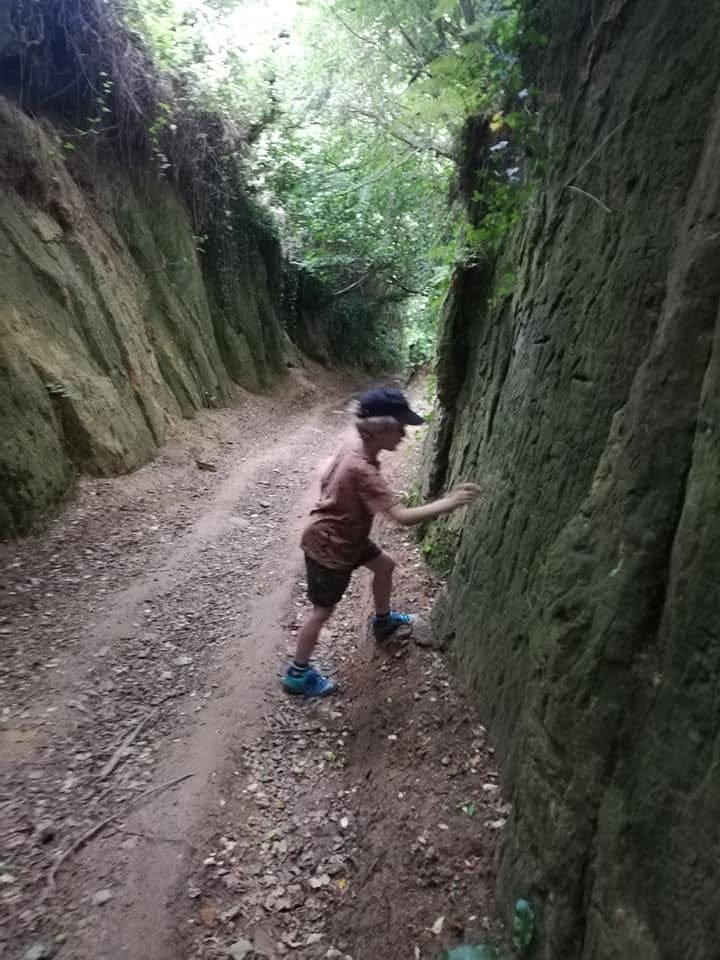

He scrambles to his feet, swipes his messy brown curls out of his eyes and gestures to the landscape around us. ‘I’ll take some more photos.’ He points to the muddy banks below and the barbed wire fence beyond. ‘Go up there a bit and explore, take more photos. He might have done that, don’t you think?’

I shrug. ‘My guess is he fell in at the weir, at Throop. Left this note, walked all that way, left the other note on the mill and decided he’d had enough and he’d go home.’

Ed nods, his brow knitted in serious thought. ‘I think so too. The bridge over the weir was wooden back then.’ He opens his book, shows me another photo, this time from the 80s. ‘See? Dangerous. They never found a body though.’

‘Isn’t his mother still alive?’

Ed nods again. ‘Yep, and most of his siblings.’

That’s right — Pip came from a large family who lived in Christchurch. He had two older brothers, one older sister, one younger sister and another baby brother. I bet his poor mother was run ragged.

‘But this is a ghost investigation,’ I remind Ed. ‘Not a missing person’s investigation.’

Ed ignores me, stuffs his book in his backpack and goes down to the water. In order to keep his project classed as local history, his teacher suggested interviewing people about the ghost sightings over the years. My guess is the teacher didn’t want Ed harassing the family or the police about the cold case of the missing Pip Collins. Better to let him scratch around after ghosts, then they can all have a laugh in the staff room after.

I walk across the fallen log in my sandals, wincing when the cold water laps over my toes, holding my arms out to either side for balance. Electric blue damselflies hover above the water in pairs, and every now and then the drone of a huge dragonfly makes me squeal and duck. I don’t fall off though and when I get back to the bank, Ed is climbing back over the barbed wire with only one scratch on his ankle to show for it.

‘What now?’ I ask, following him back up to the bridge.

‘Interviews,’ he says, flicking through the photos on his phone. ‘I’ll have everything in place then. Original newspaper reports, interviews with his family at the time, the photos, the timeline, oh, and the route he took to the mill which no one knew about until recently.’

‘Think they’ll open up the case again?’ I ask him.

He shrugs. ‘They should. No one ever saw him at the mill or on the way there or back. They should at least put it in the news, see if they can jog any memories.’

Our mission for today is the two people locally who have claimed to see a ghost that resembles poor Pip Collins.

The first is Mr Coleman; a retired gamekeeper who lives in one of the cottages on Hurn Court Lane. He’s a bit stern, always used to scare the shit out of us when we were little kids, stomping about with all his camo gear on, well trained Labradors at his heels. He’d ask if we’d seen any suspicious characters about, his dark eyes narrowed on ours.

We find him in his back garden, smoking a cigarette while he waters his runner beans. A grey-faced black Lab lies in the sun behind him. He’s still wearing his camo gear.

‘I never saw the lad,’ he relays to us once Ed has his phone recorder running. ‘Not when he was alive, anyway. They didn’t come up this way, the family. This was all unfamiliar territory to the lad, see.’

‘His mum said he ran away to teach her a lesson,’ Ed pipes up.

‘That’s what I heard too,’ nods Mr Coleman. ‘Was feeling left out when his latest sibling arrived, something like that. Decided to teach them all a lesson and ran away.’ He chuckles a little at the thought then gives us a pained look. ‘Kids were always doing things like that back then. They ran free and had fun without adult supervision. Not like you lot glued to your screens inside your houses.’

We don’t take the bait. Ed smiles politely. ‘He had run away before,’ he says and Mr Coleman nods. ‘But he had never come up to Hurn from Christchurch.’

‘So, he didn’t know the area,’ Mr Coleman goes on. ‘Expect he walked up from Fairmile Road, kept going straight across Blackwater. Traffic was lighter back then, of course. And it wasn’t unusual to see kids out on their own at that age.’ He throws us another dirty look. ‘No doubt he spotted the lane all shady and curious, and decided to cross over and wander down to the bridge. Lovely place to play. Private. Sheltered by all those trees. Kids were always playing out alone back then. Plenty of tiddlers to catch.’

‘He didn’t take his net that day,’ Ed points out. ‘Nothing was found at all. Not sweet wrappers, or even footprints.’

Mr Coleman looks sad. ‘That’s right, I remember. No sign. No trace. Apart from that note on the railings but who can be sure it was him that did it?’

‘His mother said it was his handwriting,’ I shrug.

He shrugs back. ‘No one knows for sure, but I can see why everyone thought so. Cheeky little sod thought running away was funny.’

‘What do you make of the second note that’s been found on the mill?’ asks Ed.

The old man scratches his nose. ‘I’m not sure it’s connected. The writing looks different to me. They’re having it analysed or something, aren’t they?’

‘Yes, so we might know more soon, but that would make sense wouldn’t it? That he carried on down the lane, turned left at Pig Shoot and followed the river to the weir bridge?’ Ed brings out the old photo. ‘It was dangerous back then. He could have fallen in there after writing on the mill.’

‘What did the second note say again?’

Ed shows him and reads it out at the same time. ‘It says, no one can see me.’

‘Little sod,’ sighs the old man. ‘I don’t know. S’pose we’ll have to wait to see what the experts say, but that’s not where I saw the ghost, so I’m sceptical myself.’

‘Tell us about the ghost, Mr Coleman.’

He nods and settles back on the wicker garden chair. ‘It was just the once,’ he relays, his voice low and soft. ‘Early morning. I was taking the dogs over the forest and I came up towards the bridge. There was mist on the water, I remember that, and the sun was shining through the trees. Spring time, it was. Everything in bloom.

‘And that’s when I saw this little figure standing on the bridge. He looked real to me. So real, the dogs barked and I called out to him. The railings were old and they needed replacing. I thought he might fall in. Mind you, it’s so shallow there, he’d have been all right, but still… He looked back at me, you know. I saw his little face. Pale, but he was smiling. Laughing, I think.’

Ed and I sit frozen on either side of Mr Coleman. We know the bridge and the shallows so well, we can see it perfectly inside our own heads. Though I don’t believe a word of it. Everyone knows Mr Coleman is fond of the drink.

Mr Coleman goes on to describe how he approached the boy and the boy vanished into thin air. He snaps his fingers at us. ‘Poof! Like that!’

That’s when me and Ed swap a look. I can feel the giggles rumbling to life in my guts and I know we have to get out of there soon.

‘And you have never seen the ghost again?’ Ed checks.

Mr Coleman shakes his head sadly. ‘Nope, never. But I know what I saw and I know it was a long time ago but it’s always stayed with me. The way he laughed and grinned then just vanished.’ His eyes cloud with memory as me and Ed swap another look. ‘I’ll never forget it.’

We leave him to his memories and seek out our second interviewee, Mrs Doreen Goldsmith, who lives in a retirement flat in Christchurch. It’s a long hot walk into town for Ed and me, but my brother looks ever more determined, and walks silently, refusing to be drawn into my childish musings and games.

‘I know what I saw,’ the old lady asserts as soon as we are seated beside her. She’s been wheeled outside to enjoy the sunshine, but has a knitted blanket tucked over her frail knees. She’s smiling at us, her old eyes twinkling. ‘And it wasn’t just the once. It was all the time, usually at dusk, when I was heading home. I worked in town you see, biked there and back every day. It was usually nearly dark by the time I cycled down that hill and over the bridge.’

‘That’s where you would see him?’ Ed checks.

‘Oh yes, always on the bridge, where he left the note. Always holding onto the railings and leaning over. And he would always look up when I drew near, and he would always smile and laugh.’

‘Did he ever speak to you?’

‘No.’ She looks momentarily sad about this. ‘He would only laugh. It frightened me at first, of course. I was just a girl myself. But I recognised him from the newspapers and I tried to tell the police. Everyone thought I was crazy, of course.’

‘Other people claim to have seen a ghost there too,’ I remind her.

She smiles graciously. ‘Have you seen him?’ We both shake our heads. She leans a little closer. ‘You have to be there at the right time. It was always dusk for me, when the light was fading. The low sun would be reflecting off the water and he’d appear there in the beams, you see.’

Her story is strikingly similar to Mr Coleman’s, apart from the time of the day, but after we leave Ed makes a note in his book:

Coleman — a drinker

Goldsmith — has dementia

My brother seems sad and deflated when he leave the retirement home. We are exhausted but he says he can’t go home yet, not until he has followed Pip’s route to the mill and back.

So, that’s what we do, crossing over the old mossy bridge once again, then following the lane down to Pig Shoot, across the forde, and on towards the weir and the mill. We find the new note guarded by metal railings and police tape. With his phone zoomed in to maximum, Ed snaps a picture and we stare at the words side by side, comparing it to the one at our bridge.

No one can see me.

‘Coleman might be right about one thing,’ my brother murmurs, his expression troubled. ‘There are no random capitals in this one. Other than that it looks the same though, right?’

‘Right.’ I’m tired and I want to call it quits, but a sort of fire takes over Ed’s eyes and he sets off suddenly, muttering to himself. ‘What is it?’

I struggle to keep up but Ed hurries over the weir and heads back to the forde, where another old stone bridge takes us over the water. He’s possessed, I think, watching as he clambers over the railings and drops himself into the water. It’s shallow, but cold, and he gasps as his hands curl around the railings, and his eyes skim up and down as if searching for something.

Then, my brother starts shouting. He looks insane. Stood in the water, his lower half soaked through, pointing and shouting and laughing and crying all at once.

He helps me over to see what all the fuss is about and there it is. The source of Ed’s explosive reaction. Another note.

A man is following me with a gun.

I tremble, what does this mean? Ed takes a photo, then climbs out, dragging me with him. He starts comparing the three notes while I shiver on the bridge beside him.

‘How did you know?’

‘I saw it years ago! Remember when you were about four and you had that rainbow coloured bouncy ball? And it went in the water right here?’

I shake my head. ‘No. I don’t know. Maybe.’

‘Mum and dad were on their bikes further back. I was nine. I climbed and got the ball back for you and that’s when I saw the note. Pip must have been in the water when he wrote it! I only saw it because I’d climbed in too. Mum and dad were furious with me, said it was dangerous.’

I stare at him and it slowly sinks in. ‘Bloody hell, Ed!’

‘I know, I know! It’s been bugging me since the note on the mill was found. I knew I knew something, you know? You know when there is a memory or a thought or a feeling and you just can’t grab onto it?’

‘We need to tell the police,’ I say, my arms folded over my damp clothes.

‘Man with a gun,’ Ed muses, putting his phone away. ‘Man with a gun.’

We have the same thought at the same time and turn towards each other suddenly.

Around here, the gamekeeper would have been the only person with a gun.