This is a story originally posted in my Medium publication, The Wild Writers Club!

The Shallows

July tipped into August.

It did so lazily, like the slow sticky drips from a forgotten ice cream.

The hot weather had dulled and bloated us. Like fat lazy flies we could not move. And the days all had that endless quality, like every hour was twice the length and we had stopped being ruled by clocks, and time.

We existed in our own timeless purposeless bubble. The sun had moved and taken our shade from it. The trampoline where we had lounged all afternoon was now a sun trap.

It was the heat and the boredom that drove us to the river. Not the big river, where there would be chaos and kayaks and fishermen and teenagers dunking each other under the water. We headed to the little river, to the shallows.

We strolled down the hot lane, shaded intermittently by oaks and limes and sycamores. They provided blessed shadows as our bare feet burned on the road.

No cars. No noise save the drone of a gigantic dragonfly.

We dragged sticks behind us and thought about how hot it was. It was always too hot to speak, so Pippa and I had almost given it up. Sometimes all we could think to say was how hot it was. Sometimes summer seemed to go on forever and you started to forget how to live in the normal world.

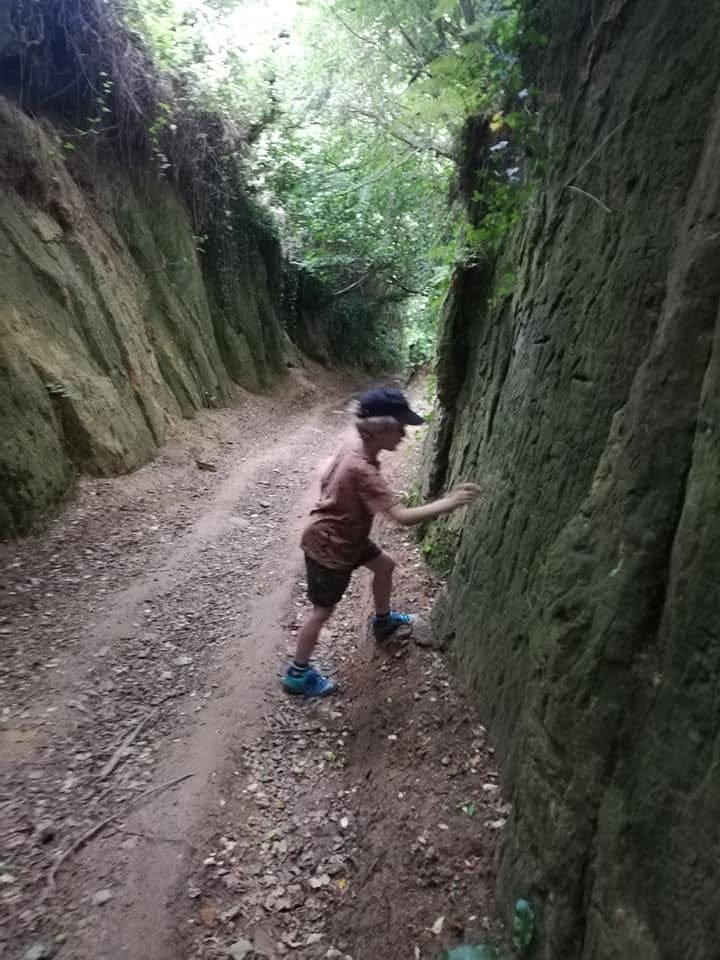

We took the left at Twisty Corners and it was still too hot to talk, despite the darkness that suddenly enveloped us from the trees above and around. They created a tunnel and we ambled down it sluggishly. Pippa was a year younger than me but we were both on the brink of something else.

‘You’re like a pair of foals,’ our dad always said, ‘all legs.’

We were caught in that no man’s land between childhood and adolescence. Everything the adults said and did suddenly annoyed us, yet we still tucked a soft toy under our arms when we went to bed at night.

We traipsed over the stone bridge, pausing lethargically to throw a stick in and watch it float out on the other side. There was nothing to say. Nothing to think. We plodded down the muddy bank, wincing as the overgrown nettles swiped our skin. And there it was. The shallows.

The water flowed slowly from under the bridge, then veered left channeling through a narrow stretch, the banks too high to climb. That way lay madness, I thought, but didn’t know why.

In front of us a great expanse of shining water undulated with the gentle current and we stood and marveled at it, at the way the light came through the canopy of hazel trees and lit up the shallows like a sprinkling of fairy lights.

The shallows had its own light; a unique blend of red and gold as the dappled sunlight broke through the leaves and filtered through water to the red earth below. We stood side by side, our toes curling into the mud, staring at it as if in a trance. Time slowed and we breathed in unison. I was about to tell Pippa I was bored when she gripped my arm and pointed.

‘What’s that under the tree?’

I looked to the right where a fallen tree stretched from one bank to the other. It came down a few years back and was slowly rotting away as the river washed over it in the winter and under it in the summer. Sometimes we’d sit there with our feet in the water, watching the tiny fish swim by as the electric blue damselflies flitted under the bridge.

Pippa’s grip tightened. I pulled away and started to wade through the water. There was something lodged under the tree. It looked like a pile of clothes, inflated by the water; dark blue material ballooning against the gentle tide.

‘Someone’s thrown rubbish in again,’ I muttered, reaching the fallen tree.

It was then that I got the prickling sensation on the back of my neck. I put a hand there, self-soothing, but the feeling persisted until I lifted my gaze and saw the man standing on the bridge. I looked back at Pippa and shrugged. She splashed towards me and we stood side by side again, a united force.

I still held a stick and poked at the bundle of clothes with it. I felt self-conscious doing it, as the man on the bridge looked on, but when I gazed up again to see if he was still watching us, he wasn’t there. I nudged my sister.

‘Where’d he go?’

She shrugged and used her own stick to help me with the bundle of clothes. We used the sticks like hooks, trying to free the bundle which had become wedged under the log. We did it lazily, carelessly, poking and jabbing at this thing that had jarred our peaceful vision of the shallows.

That was when we realised it was not just a bundle of clothes.

It suddenly sprung free and floated by. Pippa and I turned slowly to watch it go. We were weary from the heat, as if all our senses and brain functions had been slowed down by sticky sweat. We saw the blue material followed by dark legs. We saw bare feet. We didn’t see a head.

We stood in the shallows, frozen. Our arms hung by our sides, our knuckles skimming the cold water, our fingers still curled loosely around our poking sticks. We didn’t say a word as we watched it go.

It passed the deep spot, the bit that always fooled our terrier Binx when he was alive. He’d paddle out brashly before suddenly finding no land beneath his paws as it dipped away brutally, trying to drown him. He’d sputter and panic and swim back and then he’d make the same mistake again next time.

It moved faster there, the current stronger, but ultimately driving it to the left, towards the narrow channel that we knew eventually met with the huge monster of the river Stour. It was sinking too; the water and the debris were filling the materials, dragging it down.

Still, we watched, Pippa and I, not saying a word, barely breathing as if we were not really there, and I could almost believe that to be true if it weren’t for the tiny sticklebacks circling my toes. I could almost believe if I closed my eyes and then opened them again slowly, I would find myself spreadeagled on my bed with the sun slanting down on me, or face down on the trampoline, exhausted by the endless heat.

The body moved on with some speed, spinning just once as it knocked against the end of another fallen tree. That was the moment I told myself I should have moved. I should have splashed my way over to the other tree, climbed on and made my way to the end. I could have hooked it again then. I could have snagged it and stopped it and Pippa could have called the police.

But it was like I knew I never would.

None of it felt real.

It looked less like a body now, just some blue material still visible as the current drove it towards the narrow stretch. I knew if it went down there we would not be able to follow. The water was unknowable, dark depths promising no foot holds or forgiveness. The banks were steep and slippy and we could never see where it ended. There was a darkness to that place, where the shallows became the deep. We never ventured there.

I also knew if it went down there it would more than likely sink or get snagged on something again, and I knew that no one would ever find it. No one would ever know. And there was something dark and delicious about that knowing.

I thought Pippa might say something. I thought she might cry out, pull my hand or say something. But she didn’t. When I turned my head to look at her, her expression was slack and dull. There was no wonder in her eyes, only a blunted acceptance. Her forehead shone with sweat and I watched a bead of moisture form on her top lip.

When I looked back for the body, it had gone.

I heard a noise escape Pippa. A long, low exhalation of breath.

Then another noise behind us.

I looked over my shoulder and the man was there again. He was wearing a blue shirt and dark trousers. He was staring right at us, some kind of intent in his expression that told me he was about to open his mouth and speak to us, and for some inexplicable reason, this possibility filled me with dread.

I gripped my sister’s hand and yanked her until she moved. Together we splashed back to the flat sandy bank, still holding our sticks. We didn’t look at the man as we crept away, skirting the large clutch of nettles that surrounded the ash tree. On the other side, I peeked out like a rabbit checking the land from its burrow. The bridge was clear. The man was gone.

We started running, our bare wet feet slapping across the old stony bridge where the man had stood just moments before.

Still, we didn’t speak. To speak would be to give it a reality I knew instinctively to avoid. As I rushed us home, as Pippa and I ran hand in hand up the sun-baked lane, the sun punishing us every time there was a gap in the shade from the oaks, I felt a roaring dread that Pippa would open her mouth and speak. I thought perhaps I would punch her in the mouth if she tried to.

By the time we reached home and shoved open the wooden gate, we were drenched in sweat and feeling giddy. We closed it behind us and felt the dread drop away from us. We threw down our sticks and didn’t look at each other as we made our way around to the back garden.

The trampoline was still in full sun so we plodded over to the far right corner of the garden without speaking. There was always this unsaid thing between me and Pippa. We could go hours without talking and still be completely in tune with each other. She was the one who dragged a blanket from the washing line, bone dry and starched stiff from the sun. She threw it on the grass under the sycamore tree and we dropped down on our bellies, our feet kicking at the sky as we buried our faces in our sticky arms.

‘Everything all right?’ we heard a voice call from the house.

We raised our heads long enough to see that it was our father, home early from work, his glasses pushed up on his head as he squinted across the garden at us.

I met Pippa’s eye and knew just what she was thinking. It was so tempting not to answer him. It would be so easy just to smirk at each other, lie back down and ignore him. And we knew he would just accept it. Just shrug his shoulders as if it must be his own fault. Or worse, he would wander over, hands in pockets, hopeful expression on his face.

I decided to end it before it began. I didn’t know why he seemed scared of us lately but it was tiring to say the least. I didn’t want him to amble over to us and try to evoke conversation. It was always too hot and there was nothing to say.

I waved at him. ‘Fine, Dad! We’re just tired!’

‘Been out all day gallivanting, eh?’ he yelled back.

Pippa shot me a scowl. ‘Gallivanting?’ she hissed under her breath.

‘Yeah, something like that!’

Satisfied, he waved again then ducked back inside the house. We both knew he would reappear at some point, perhaps carrying cold drinks on a tray in an attempt to bribe us into words.

We dropped our heads, closed our eyes and breathed. I felt the relentless sun beating down on everything and knew it was too hot to talk of it, too hot to even think of it.

And more than anything, it was simply too late.